Aviation History: September 6, 1522

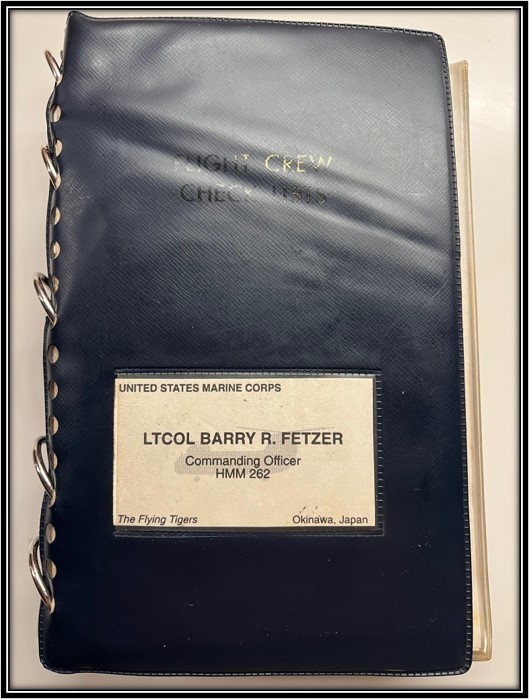

Contributor: Barry Fetzer

The ease at which we board a cruise ship or a jet airliner today and sail the “Seven seas” or circumnavigate the globe by air, well, they mask the great risk and difficulties of those early explorers who led us to these benefits…these gifts…these blessings…of the modern world. We should remember and appreciate those explorers and their difficulties every time we board an aircraft.

On this day in aviation history, September 6, 1522, one of explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s five ships—the Victoria—arrived at Sanlúcar de Barrameda in Spain after three years at sea amidst much hardship and death, thus completing the first circumnavigation of the world.

Before we continue with the story about Magellan, this is, after all, a column about aviation history, right? So, what does Ferdinand Magellan and his sailing 400 years before the Wright Brothers have to do with aviation?

Let’s take the sailing part first: The observation of the effects of sailing and the propulsion achieved by wind blowing against and passing over a sail, ultimately led to the development of the aircraft wing and of aerial flight. In 2009 author Peter Garrison in Flying Magazine published an article entitled “Airfoils, a short history”. In this column Garrison wrote, “Let’s be frank. We don’t really need airfoils. Model planes with flat sheets of balsa wood for wings fly nicely; so do airplanes made of folded paper, and bumblebees and butterflies. A flat sheet makes a perfectly serviceable wing.

That flat surfaces in the wind could produce the sideways force that we now call lift was a very ancient observation. Two early applications of it, the windmill and the fore-aft rigged sail, date back at least 800 years. It was also perfectly evident to any thinking person that what kept birds and bats aloft was the large flat surfaces attached to their arms. Neither the feathers of birds nor the fabric of sails and windmill blades had any thickness to speak of, and so the earliest lifting surfaces were just that: surfaces.”

Sails were, therefore, the first lifting surfaces…and led to wings and airfoils. And ultimately, luck us, to Moore County Airport!

So, ship’s captain, explorer, navigator, and sailor Christopher Columbus who “In 1492 sailed the ocean blue” and the subject of this aviation vignette, Ferdinand Magellan, both added steps—just as all early sailors did from the ancient Māori people who populated New Zealand, the ancient Greeks and the Vikings—leading to our ability to hop aboard an aircraft, at will, and safely fly around the world.

But the other part of Magellan related to aviation is more modern. His name was “pirated” (yes, that is a bit of a pun and was intended), perhaps nearly as early as aviation itself, by military aviators for use as a codeword. Unfortunately, for Magellan, his codeword-associated name is not necessarily a “positive” one.

Pictured below is my flightcrew checklist binder, this particular one about 30-years-old that was replacement for one I had since the mid-1970’s. Inside this “analog” device that many older military aviators carried with them and will remember, was what we called our “brains”, a compilation of aviation-related facts and details that we did not have to memorize (at least not all of them) but were needed from time-to-time during operations. We’d carry this checklist inside our helmet bag as a ready reference.

My checklist binder includes a list of “prowords and codewords”, also pictured below. According to Wikipedia, “In aviation, ‘prowords’ or “procedure words” are words or phrases limited to radio telephone procedure used to facilitate communication by conveying information in a condensed, standard verbal format. They are voice versions of the much older procedural signs for Morse code which were first developed in the 1860s for Morse telegraphy, and their meaning is identical. The NATO communications manual ACP-125 contains the most formal and perhaps earliest modern (post-World War II) glossary of prowords, but its definitions have been adopted by many other organizations, including the United Nations Development Programme, the U.S. Coast Guard, US Civil Air Patrol, US Military Auxiliary Radio System, and others.

Examples of prowords include ‘Roger’, which means, ‘I have received your last transmission satisfactorily’, ‘Over’, which means ‘This is the end of my transmission to you and a response is necessary. Go ahead: transmit.’, and ‘Out’, which means ‘This is the end of my transmission to you and no answer is required or expected.’”

Note the codeword highlighted by the arrow in the second photograph of my list of prowords and codewords, below. “Magellan” is (or was) the codeword for “check your navigation” a codeword used most often by “dash-two” or the wingman in a formation flight who used this codeword to advise the “lead” that his navigation may be off.

Magellan, before he was unfortunately killed in the Philippines during his squadron’s (of sailing ships) circumnavigation of the earth, actually did very well in navigating, especially considering that accurate determination of Longitude was still two hundred-plus years away.

So why was Magellan’s name unceremoniously associated by military aviators with poor navigation? Perhaps it was a misunderstanding of history. Or perhaps it was a “witticism” or a memory cue of an early military aviator to take a name like Magellan’s who was obviously associated with a historic and positive event of being the first to circumnavigate the earth, and turn it into a negative, a form of retrogression (the opposite of the literary technique of amelioration) similar to how the female name “Karen” has been retrogressed from a neutral or positive to a negative connotation.

Fetzer family photographs.

The last codeword cut off in the above photo is “winter”, which meant “cold landing zone”, or in other words, “no known enemy in range of our vulnerable helicopters and troops”.

Ah, but I digress. Let’s get back to the purpose of today’s vignette, courtesy of History. com: “On September 6, 1522, one of explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s five ships—the Victoria—arrived at Sanlúcar de Barrameda in Spain after three years at sea amidst much hardship and death, thus completing the first circumnavigation of the world. The Victoria was commanded by Basque navigator Juan Sebastian de Elcano, who took charge of the vessel after Magellan was killed in the Philippines in April 1521. During a long, hard journey home, the people on the ship suffered from starvation, scurvy, and harassment by Portuguese ships. Only Elcano and 21 other passengers survived to reach Spain in September 1522.

On September 20, 1519, Magellan set sail from Spain in an effort to find a western sea route to the rich Spice Islands of Indonesia. In command of five ships and 270 men, Magellan sailed to West Africa and then to Brazil, where he searched the South American coast for a strait that would take him to the Pacific. He searched the Rio de la Plata, a large estuary south of Brazil, for a way through; failing, he continued south along the coast of Patagonia. At the end of March 1520, the expedition set up winter quarters at Port St. Julian. On Easter day at midnight, the Spanish captains mutinied against their Portuguese captain, but Magellan crushed the revolt, executing one of the captains and leaving another ashore when his ship left St. Julian in August.

On October 21, he finally discovered the strait he had been seeking. The Strait of Magellan, as it became known, is located near the tip of South America, separating Tierra del Fuego and the continental mainland. Only three ships entered the passage; one had been wrecked and another deserted. It took 38 days to navigate the treacherous strait, and when ocean was sighted at the other end Magellan wept with joy. He was the first European explorer to reach the Pacific Ocean from the Atlantic. His fleet accomplished the westward crossing of the ocean in 99 days, crossing waters so strangely calm that the ocean was named ‘Pacific,’ from the Latin word pacificus, meaning “tranquil.” By the end, the men were out of food and chewed the leather parts of their gear to keep themselves alive. On March 6, 1521, the expedition landed at the island of Guam.

Ten days later, they dropped anchor at the Philippine Island of Cebu–they were only about 400 miles from the Spice Islands. Magellan met with the chief of Cebú, who after converting to Christianity persuaded the Europeans to assist him in conquering a rival tribe on the neighboring island of Mactan. In subsequent fighting on April 27, Magellan was hit by a poisoned arrow and left to die by his retreating comrades.

After Magellan’s death, the survivors, in two ships, sailed on to the Moluccas and loaded the hulls with spice. One ship attempted, unsuccessfully, to return across the Pacific. The other ship, the Victoria, continued west under the command of Juan Sebastian de Elcano. The vessel sailed across the Indian Ocean, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and arrived at the Spanish port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda on September 6, 1522, becoming the first ship to circumnavigate the globe. The Victoria then sailed up the Guadalquivir River, reaching Seville a few days later.

Elcano was later appointed to lead a fleet of seven ships on another voyage to Moluccas on behalf of Emperor Charles V. He died of scurvy enroute.”

So, thanks to the early sailors who gave us aerial flight…and a code word to check our navigation. We owe them a debt of gratitude.