Aviation History

Author: Barry R. Fetzer

Today’s historical aviation vignette comes from my memories of tracking an arc (verses a straight line) to a Non-Directional Beacon, one of the best methods (we found, at least, flying multi-mission CH-46 helicopters in the Marines) to get to where we were intending to go. Of course, this low-tech method of navigating precedes the advent of GPS and, other, more modern and accurate methods of navigation. But it was one of the best ways to get to where you were going, in my opinion at least.

We had little books in the cockpit with all the AM frequencies of radio stations in towns so we could navigate to those towns. Those were the days when active-duty Marine CH-46 squadrons (at MCAS New River (Jacksonville, NC) where I was stationed) stood “SAR-Medivac” duty and would support local governments by flying to accident sites and to hospitals to transport accident victims from accident sites and preemies and other patients to trauma centers or to search for lost boaters, swimmers, or hikers.

I don’t know why the Marines stopped flying those kinds of missions…those missions likely helped with recruiting and good will between our Nation’s citizens and her Marines. Did the Marines stop because of costs? Unwanted competition with emerging civilian rescue helicopter companies? A pull back from “traditional” duties and responsibilities no longer accomplished by Marines (like mess duty and lawn cutting), duties that shifted to contractors?

By the way, here in the Sandhills, we use Fort Bragg (soon to be renamed Fort Liberty) for our commissary, PX, and medical privileges. Soldiers at Fort Bragg can routinely be seen mowing the grass and stocking the shelves in the commissary and PX, duties being accomplished here by soldiers that I haven’t seen in years being accomplished by Marines on Marine Corps bases.

Anyway, I digress. Using the Automatic Direction Finding/Non-Direction Beacon (ADF/NDB) system to navigate to the hospitals and accident sites was almost better than flying low enough to determine the name of the town you were flying over by reading its name on the town’s water tower. Plus, win-win, you could listen to the top 40 while flying!

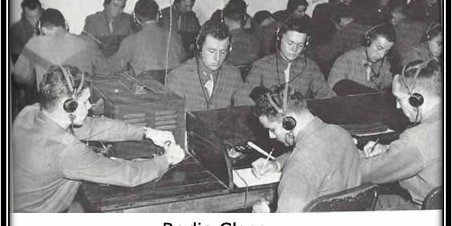

We had to learn Morse Code at naval flight school in the 70’s because, amongst other reasons for memorizing those dots and dashes, NDB’s transmitted their identification (even shipboard NDB’s) by Morse Code.

Photo courtesy of the WWII Flight Training Museum.

Pure NDB stations (as opposed to AM radio stations that could also be received on our helicopter’s ADF equipment) were intended for aerial navigation purposes and to conduct instrument approaches to airports and aircraft carriers. These NDB’s transmitted their identification by Morse Code so you could identify, with certainty, that you had the correct NDB to which to navigate.

More importantly, some of you may remember Admiral Jeramiah Denton, a POW during the Vietnam War, who used Morse Code to get a message out to America, Morse Code he learned in Pensacola (and was tested on comprehension), just as all we naval aviators did at one time. Below column from the Tampa Bay Times, published March 30, 2014 recounts his experience as a POW:

The POW who knew he could endure anything

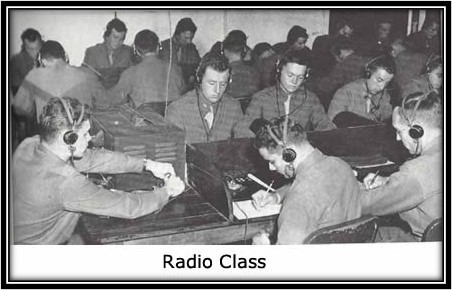

Jeremiah Denton in the 1966 interview where he blinked the word “torture” in Morse code. It provided the first confirmation that American POWs were being tortured by the North Vietnamese.

Courtesy of the National Archives

Jeremiah Denton, a Navy pilot who survived nearly eight years of captivity in North Vietnamese prisons, and whose public acts of defiance came to embody the sacrifices of American POWs, died last week (March, 2014) at a hospice in Virginia Beach. He was 89.

Millions of Americans came to see his heroism in a television appearance broadcast on the evening news in 1966 during the Vietnam War. Orchestrated by the North Vietnamese as propaganda, Denton appeared in his prison uniform and blinked the word “torture” in Morse code — a secret message to U.S. military intelligence for which he later received the Navy Cross.

Denton was shot down south of Hanoi on July 18, 1965. A former test pilot — and the father of seven — he was a commander at the time and was flying an A-6 Intruder on a bombing mission. He ejected and was captured.

Over the next seven years and seven months, Denton was incarcerated in prisons including the infamous Hoa Lo complex, also known as the Hanoi Hilton, and the facility dubbed “Alcatraz” that was reserved for the most willful resisters.

Denton spent four years in solitary confinement. Living in roach- and rat-infested conditions, he endured starvation, delirium and torture sessions that sometimes lasted days.

In one such session, his captors placed across his shins a nine-foot-long, cement-filled iron bar, he recalled in his memoir, When Hell Was in Session. One torturer “stood on it, and he and the other guard took turns jumping up and down and rolling it across my legs,” Denton wrote. “Then they lifted my arms behind my back by the cuffs, raising the top part of my body off the floor and dragging me around and around. This went on for hours.”

Ten months into his imprisonment, Denton was ordered to submit to an interview with a Japanese reporter. He said the North Vietnamese tortured him before the meeting in an effort to compel him to assist with their Communist propaganda.

In the footage, Denton walks through a doorway, bows and then, with evident discomfort, takes his seat in a chair. Hunched over, he clasps his hands. Looking into the camera lights as he speaks, he blinks his eyes hard and repeatedly, in a manner that to an untrained observer might have seemed involuntary — and that in Morse code spelled t-o-r-t-u-r-e.

Another torture session followed.

Denton was among the highest-ranking officers to be taken prisoner in Vietnam and retained his full sense of responsibility toward his men. “I put out the policy that they were not to succumb to threats, but must stand up and say no,” he told the New York Times.

Denton and hundreds of other POWs were released in 1973, shortly after the signing of the Paris Peace Accords that helped end U.S. involvement in the war. He retired from the Navy in 1977 as a rear admiral.

Denton was a native of Alabama, where in 1980 he became the state’s first Republican to win election to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction.

Years later, Denton reflected on his survival in North Vietnam.

“If I had known when I was shot down that I would be there more than seven years, I would have died of despondency, of despair,” he told Investor’s Business Daily. “But I didn’t. It was one minute at a time, one hour, one week, one year and so on. If you look at it like that, anybody can do anything.”

Talk about an arc! I just took the Great Circle Route to get to today’s vignette, the first Morse Code transmission.

From History.com: “On May 24, 1844 in a demonstration witnessed by members of Congress, American inventor Samuel F.B. Morse dispatched a telegraph message from the U.S. Capitol to Alfred Vail at a railroad station in Baltimore, Maryland. The message—“What Hath God Wrought?”—was telegraphed back to the Capitol a moment later by Vail. The question, taken from the Bible (Numbers 23:23), had been suggested to Morse by Annie Ellworth, the daughter of the commissioner of patents.

Morse, an accomplished painter, learned of a French inventor’s idea of an electric telegraph in 1832 and then spent the next 12 years attempting to perfect a working telegraph instrument. During this period, he composed the Morse code, a set of signals that could represent language in telegraph messages, and convinced Congress to finance a Washington-to-Baltimore telegraph line. On May 24, 1844, he inaugurated the world’s first commercial telegraph line with a message that was fitting given the invention’s future effects on American life.

Just a decade after the first line opened, more than 20,000 miles of telegraph cable crisscrossed the country. The rapid communication it enabled greatly aided American expansion, making railroad travel safer as it provided a boost to business conducted across the great distances of a growing United States.”

And for those wanting bit more, below is an article about the ADF/NDB system of navigational aids (NAVAIDS) that many of us “aged” aviators navigated by in-flight (and through which we also listened to local AM radio stations while flying).

ADF/NDB by Sarina Houston from https://www.liveabout.com/the-adf-ndb-navigation-system-282773

“The ADF/NDB navigation system is one of the oldest air navigation systems still in use today. It works from the simplest radio navigation concept: a ground-based radio transmitter (the NDB) sends an omnidirectional signal to an aircraft loop antenna. The result is a cockpit instrument (the ADF) that displays the aircraft position relative to an NDB station, allowing a pilot to “home” to a station or track a course from a station.

ADF Component

The Automatic Direction Finder (ADF) is the cockpit instrument that displays the relative direction to the pilot. Automatic direction finder instruments receive low and medium frequency radio waves from ground-based stations, including nondirectional beacons and instrument landing system beacons. They can even receive commercial radio broadcast stations.

The ADF receives radio signals with two antennas: a loop antenna and a sense antenna. The loop antenna determines the strength of the signal it receives from the ground station to determine the direction of the station, and the sense antenna determines whether the aircraft is moving toward or away from the station.

NDB Component

The non-directional beacon (NDB) is a ground station that emits a constant signal in every direction, also known as an omnidirectional beacon. An NDB signal operated on a frequency between 190-535 KHz does not offer information on the direction of the signal, just the strength of it.

Signals move over the ground, following the curvature of the earth. NDB stations are classified into four groups based on the beacon range in nautical miles.

Compass locator—15

Medium Homing—25

Homing—50

High Homing—75

ADF/NDB Errors

Aircraft flying close to the ground and the NDB stations will get a reliable signal despite the signal still being prone to the following errors:

*Ionosphere error: Specifically, during periods of sunset and sunrise, the ionosphere reflects NDB signals back to earth, causing fluctuations in the ADF needle.

*Electrical interference: In areas of high electrical activity, such as a thunderstorm, the ADF needle will deflect toward the source of electrical activity, causing erroneous readings.

*Terrain errors: Mountains or steep cliffs can cause bending or reflecting of signals. Pilots should disregard erroneous readings in these areas.

*Bank error: When an aircraft is in a turn, the loop antenna position is compromised, causing the ADF instrument to be off balance.

Practical Use

Pilots have found the ADF/NDB system to be reliable in determining position, but for a simple instrument, an ADF can be very complicated to use. To begin, a pilot selects and identifies the appropriate frequency for the NDB station on his ADF selector.

The ADF instrument is typically a fixed-card bearing indicator with an arrow that points in the direction of the beacon. Tracking to an NDB station in an aircraft can be done by “homing,” which is simply pointing the aircraft in the direction of the arrow.

With wind conditions at altitudes, the homing method rarely produces a straight-line to the station. Instead, it creates more of an arc pattern, making homing a rather inefficient method, especially over long distances.

Instead of homing, pilots are taught to “track” to a station using wind correction angles and relative bearing calculations. If a pilot is headed directly to the station, the arrow will point to the top of the bearing indicator, at 0 degrees. Here’s where it gets tricky, while the bearing indicator points to 0 degrees, the aircraft’s actual heading will usually be different. A pilot must understand the differences between relative bearing, magnetic bearing, and magnetic heading to properly utilize the ADF system.

In addition to constantly calculating new magnetic headings based on relative magnetic bearing, if we introduce timing into the equation—in an effort to estimate time en route, for example—there is even more calculating required.

Here is where many pilots fall behind. Calculating magnetic headings is one thing, but calculating new magnetic headings while accounting for wind, airspeed, and time en route can be a large workload, especially for a beginning pilot.

The workload associated with the ADF/NDB system can be laborious and many pilots have stopped using it. With new technologies like GPS and WAAS so readily available, the ADF/NDB system is becoming an antiquity, and some have already been decommissioned by the Federal Aviation Administration.”

Onward and upward!