Crossing the Pond

Contributor: Barry Fetzer

Sources: Oleg Makarenko, Simplyflying.com, and History Press

It’s hard to imagine a world without commercial jet aircraft. But, like everything, there was a first and, in this case, it was not in America, arguably the world’s most prolific aviation innovator. It was our friends in Great Britain who were the first to test a commercial jet airliner as described below by History.com.

We humans tend to want everything faster. And then when we get it, we want it faster, still. Commercial jets have vastly shortened trips to and from everywhere but let’s focus on America (New York) to Great Britain (London). It took 15 days in an 1830’s steamship, bettered a century later in 1936 by the RMS Queen Mary cruise ship, taking just five days. Today, going on another century later? You couldn’t get a regularly scheduled cruise ship to England. But what’s the quickest trip “across the pond?”

According to aviation researcher Oleg Makarenko, “The fastest supersonic flight record was set by a BAC Concorde in 1996. It reached London from New York City in 2 hours and 56 minutes flying at the speed of 1,350 miles per hour. As far as subsonic flights go, the record is held by a British Airways Boeing 747 which made it from New York City to London in 4 hours and 56 minutes in 2020. On average, this flight would take around 7 hours. The top speed of a 747 is roughly 600 to 615 mph but the BA112 ‘hitched a ride’ on a strong jet stream and a 200+mph tail wind thus helping it hit the speed of 825 miles per hour on its record setting flight.”

The path to routine and rapid trips to Europe from America was not an easy one. According to Simplyflying.com, “Imperial Airways was the first airline to investigate using the Short Empire seaplane to cross over from Ireland to the Americas in 1937. Not to be left out on this venture, Pan American flew the opposite way with a Sikorsky S-42. Both airlines would begin regular seaplane routes soon thereafter.

Sikorsky S-42 (Courtesy National Air and Space Museum)

Sikorsky S-42 (Courtesy National Air and Space Museum)

This initial journey to Europe took 20 hours, 21 minutes at an average ground speed of 144 miles per hour (232 km/h). The Short Empire seaplane didn’t actually have enough power to lift itself off the ground with the fuel needed for the journey, so it was actually carried by a bigger aircraft to the right attitude and then released.” How’d you like to take that flight?

Rigid airships were the first to make the transatlantic flight. Again from Simplyflying.com, “From October 1928, vast rigid airships crossed the Atlantic from Germany to New York. However, in 1937 this fantasy of ‘floating cruise ships’ ended with the German Hindenburg and the British R101 rigid airship disasters.”

According to the History Press, “In 1936 and 1937, the Zeppelin Hindenburg was the quickest way to travel between the United States and Europe. LZ-129 Hindenburg dazzled the world as the latest in a series of advances in transoceanic transportation. A hundred years earlier, Brunel’s steamship Great Western, steaming at 9 knots, crossed the Atlantic in fifteen days. By 1890, the Cunard liners Etruria and Umbria crossed the Atlantic at 19 knots in about a week. By 1936 – the year Hindenburg first flew – Cunard’s RMS Queen Mary sped at 30 knots, but it still took about five days to transport goods and passengers from Europe to America.

While Queen Mary steamed on the ocean below, Hindenburg carried passengers from shore to shore in a matter of hours; the airship’s fastest crossing was just forty-three hours. ‘Two Days to Europe!’ boasted Hindenburg’s brochures and posters.

In contrast with her rivals on the ocean, no Hindenburg passenger ever complained of seasickness. Cunard Line’s massive Queen Mary was over 80,000 tons and more than a 1,000ft long, but still moved so badly in rough weather that some said it could ‘roll the milk out of tea’.”

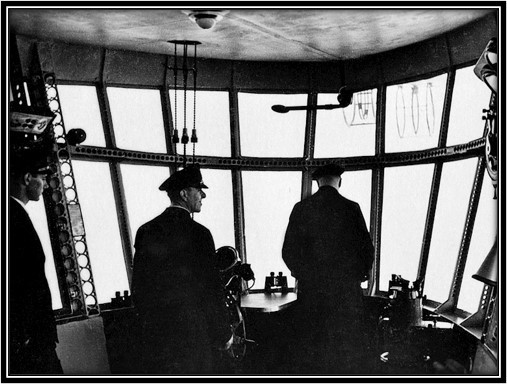

The Hindenburg cockpit (Courtesy History Press)

The Hindenburg cockpit (Courtesy History Press)

But it wasn’t just the “milk rolling out of the tea” that provoked advancements in transportation technology. It was the need for speed. Just over a decade later, according to History.com, “On July 27, 1949, the world’s first jet-propelled airliner, the British De Havilland Comet, made its maiden test-flight in England. The jet engine would ultimately revolutionize the airline industry, shrinking air travel time in half by enabling planes to climb faster and fly higher.

The Comet was the creation of English aircraft designer and aviation pioneer Sir Geoffrey de Havilland (1882-1965). De Havilland started out designing motorcycles and buses, but after seeing Wilbur Wright demonstrate an airplane in 1908, he decided to build one of his own. The Wright brothers had made their famous first flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903. De Havilland successfully designed and piloted his first plane in 1910 and went on to work for English aircraft manufacturers before starting his own company in 1920. De Havilland Aircraft Company became a leader in the aviation industry, known for developing lighter engines and faster, more streamlined planes.

In 1939, an experimental jet-powered plane debuted in Germany. During World War II, Germany was the first country to use jet fighters. De Havilland also designed fighter planes during the war years. He was knighted for his contributions to aviation in 1944.

The de Havilland Comet in 1952. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

The de Havilland Comet in 1952. (Courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

Following the war, De Havilland turned his focus to commercial jets, developing the Comet and the Ghost jet engine. After its July 1949 test flight, the Comet underwent three more years of testing and training flights. Then, on May 2, 1952, the British Overseas Aircraft Corporation (BOAC) began the world’s first commercial jet service with the 44-seat Comet 1A, flying paying passengers from London to Johannesburg. The Comet was capable of traveling 480 miles per hour, a record speed at the time. However, the initial commercial service was short-lived, and due to a series of fatal crashes in 1953 and 1954, the entire fleet was grounded. Investigators eventually determined that the planes had experienced metal fatigue resulting from the need to repeatedly pressurize and depressurize. Four years later, De Havilland debuted an improved and recertified Comet, but in the meantime, American airline manufacturers Boeing and Douglas had each introduced faster, more efficient jets of their own and become the dominant forces in the industry. By the early 1980s, most Comets used by commercial airlines had been taken out of service.”