MISTY 40 FAC has Flown His Final Flight

Contributor: Barry Fetzer

Nine days ago, we lost one of the our most accomplished aviators, Dick Rutan. The following tribute is by Jim Moore, Managing Editor-Digital Media for AOPA.

A decorated war hero and aviation pioneer, Dick Rutan, who “played an airplane like someone plays a grand piano,” in the words of his younger brother, met death on his own terms on May 3, with his wife and family by his side. His life begun 85 years ago in Loma Linda, California, included setting what his family called “the last great aviation record” with the nonstop flight around the world in the Rutan Model 76 Voyager, designed by younger brother, Burt Rutan, in 1986.

Dick Rutan’s life ended on May 3 in a hospital in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, with his family and longtime friend Bill Whittle present. Whittle told the Associated Press that Rutan opted not to endure a second night on oxygen being administered to treat a lung infection. Rutan flew 325 combat missions in Vietnam, part of an elite group of fighter pilots with the callsign “Misty” and the unenviable assignment of loitering for hours over enemy antiaircraft units, and enemy fire on one occasion forced him to eject from his North American F–100 Super Sabre. A second successful ejection was necessitated by mechanical failure over England. Rutan retired from the U.S. Air Force as a lieutenant colonel, having been awarded medals including the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross (twice), and Purple Heart, though he was by no means finished flying.

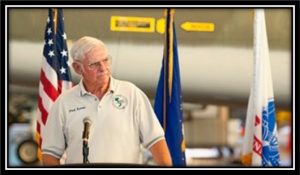

Dick Rutan, Vietnam War veteran and U.S. Air Force ‘Misty Four-Zero’ fighter pilot, speaks to the audience during a dedication ceremony held at the Pacific Aviation Museum Pearl Harbor on Ford Island, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam in Hawaii, on October 30, 2014. ‘Misty’ pilots reunited for a panel discussion, a book signing event, and the dedication of a restored North American F-100 Super Sabre, marking the fiftieth anniversary of the Vietnam War. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Diana Quinlan.

According to a fellow Misty Forward Air Controller, “when it was forbidden to fly over Hanoi, Rutan went down on the deck over the sea and blasted over the Hanoi Hilton with full afterburner to the let the POW’s know that we still cared. This very much could have been a court martial offense, but no one said a thing.

The Rutan brothers worked together on many projects, including Voyager—Burt designing cutting-edge aircraft in bunches, Dick flying them. On December 14, 1986, Dick Rutan and copilot Jeana Yeager, who helped build the aircraft with the Rutan brothers and crew chief Bruce Evans, launched Voyager from Edwards Air Force Base in California at 8:01:44 a.m. Pacific time, and flew west, nonstop, for nine days, three minutes, and 44 seconds, returning to land at Edwards, shattering the record for unrefueled flight and earning a Presidential Citizens Medal, presented to the two pilots and the aircraft’s designer by President Ronald Reagan.

The ‘Voyager’ aircraft circles before landing at Edwards Air Force Base in California on December 23, 1986, completing a record-breaking, nonstop unfueled flight around the world. The aircraft’s takeoff weight was more than 10 times the structural weight, but its drag was lower than almost any other powered aircraft. The nine-day, three-minute, 44-second flight nearly doubled the previous distance record set in 1962 by a U.S. Air Force Boeing B-52. Photo courtesy of NASA.

Now in the collection of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Voyager’s historic flight nearly ended before it began. Fully loaded with fuel for the first time, the carbon fiber wings drooped and scraped the runway as the aircraft accelerated with painful slowness to flying speed, damaging the winglets.

Burt Rutan, aboard a chase aircraft with Mike Melvill (who would later fly another Rutan design, SpaceShipOne, into space and open the age of civilian space flight), observed the damage and advised his brother and Yeager that the aircraft remained within limits, and the flight could continue.

Aboard Voyager, Rutan had been unable to see the dragging wingtips from the cramped confines of the pilot’s seat, and he used more than 14,000 feet of runway before rotating.

“And then, the velvet arm really came in,” Burt Rutan said later, employing an oft-used description of his brother’s masterfully smooth technique, according to the AP. “And he very slowly brought the stick back and the wings bent way up, some 30 feet at the wingtips, and it lifted off very smoothly.”

“We had the freedom to pursue a dream, and that’s important,” Dick Rutan said at the ceremony, according to the AP. “And we should never forget, and those that guard our freedoms, that we should hang on to them very tenaciously and be very careful about some do-gooder that thinks that our safety is more important than our freedom. Because freedom is awful difficult to obtain, and it’s even more difficult to regain it once it’s lost.”