On this day in aviation history: Pancho Villa and the First Aero Squadron

Contributor: Barry Fetzer

Sources: History.com

Being the first at something is a pretty special accomplishment. Being named “the First” and then actually “being” the first is really unique.

Except, I suppose, for being first-born in my family, I’ve never been first at anything and if I were ever have had a chance to be first at something…well…those days are long gone at my age.

But others had that chance, a chance that has bypassed me. According to History.com, on this day in aviation history, “Eight Curtiss ‘Jenny’ planes of the First Aero Squadron took off from Columbus, New Mexico, in the first combat air mission in U.S. history. The First Aero Squadron, organized in 1914 after the outbreak of World War I, was on a support mission for the 7,000 U.S. troops who invaded Mexico to capture Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa.

“On March 9, 1916, Villa, who opposed American support for Mexican President Venustiano Carranza, led a band of several hundred guerrillas across the border on a raid of the town of Columbus, New Mexico, killing 17 Americans. On March 15, under orders from President Woodrow Wilson, U.S. Brigadier General John J. Pershing launched a punitive expedition into Mexico to capture Villa. Four days later, the First Aero Squadron was sent into Mexico to scout and relay messages for General Pershing.”

One of new 1st Aero Squadron’s Curtiss JN2s ‘Jennys’ at the Signal Corps Aviation School, North Island California, 1913.

Photo courtesy 20th Century Aviation Magazine.

“The 1st Aero Squadron, or the 1st Reconnaissance Squadron, is the oldest US military flying unit. It was formed March 5, 1913, and has an unbroken heritage of over 100 years! General John J. Pershing ordered the 1st Aero Squadron to become the first aviation unit to participate in military action.

“In February, 1913, tension with Mexico was increasing. President William Taft ordered the 2nd Army Division to mobilize a defense against Mexico. On March 5, a small group of Officers and enlisted men were formed into the First Aero Squadron, assigned to the 2nd Division, which was commanded by Signal Corps Captain Charles de Forest Chandler. Nine airplanes were assigned to the squadron, which was formed into two companies. Company A had 3 pilots, 4 airplanes, and 24 enlisted men; company B had 3 pilots, 27 enlisted men and 5 airplanes. The pilots were all Army Officers, with the rank of 1st or 2nd Lieutenant.

“While the airplanes were ‘cutting edge’ at the time, very little scientific testing had gone their development. Some of the airplanes were actually made by the pilots themselves. Crashes were common, and repair was time-consuming and difficult. The fatality rate was high among the pilots. Flight lessons were almost unheard of, and frequently consisted of general guidelines given on the ground, and individual practice. One of the early pilots, Capt. Benjamin D. Foulois, was given instruction from Orville Wright, by mail!

“On March 9, 1916, more than 1,000 of Pancho Villa’s horsemen crossed the border at Columbus, New Mexico and raided the town. Seventeen Americans were killed as they looted and burned the town. President Wilson immediately asked permission from President Carranza of Mexico to send troops into Mexico. Carranza reluctantly gave permission, ‘for the sole purpose of capturing the bandit Villa.’ With that permission, Wilson ordered a ‘Punitive Expedition,’ and told General Pershing to ‘pursue and disperse’ Villa’s forces. Pershing thought this would be a good opportunity to use the airplanes and he ordered the 1st Aero Squadron to Columbus to set up operations. He planned to use the aircraft for observation support of the ground forces.

“The greatest weakness of the Squadron was its lack of airplanes. Those observing operations in WWI in Europe, understood that an aviation squadron needed a minimum of 12 operational airplanes, 12 replacements, and a reserve of 12, 36 airplanes in all. The 1st Aero Squadron had only 8 Curtiss JN-3 airplanes, and was desperately short of spare parts.

“The Squadron arrived in Columbus on March 15, only with 8 airplanes, 11 pilots, 82 enlisted men, and flew their first reconnaissance sortie on the 16th. That was the first time American aircraft were used in an actual military operation.

“Three days later, on March 19th, the squadron was ordered to report ‘without delay’ to Pershing’s headquarters in Casas Grandes, Mexico. The pilots departed early that evening. Having little actually night flying experience, darkness proved to be a major problem for the pilots. One airplane made it to headquarters that night. The next morning two aircraft landed. One airplane had returned to Columbus, and two others were missing. They then discovered another problem that could not be overcome. These airplanes, with their 90 horsepower engines were no match for the mountains. They simply could not climb high enough to cross the 10,000 – 12,000’ peaks. In addition, the strong turbulent winds meant they could not fly through the passes. The frequent dust storms played havoc with the engines, making it almost impossible to fly, and the unrelenting heat de-laminated the wooden propellers!

“Due to weather and maintenance problems, and the airplane’s lack of power, many missions simply could not be accomplished. Captain Foulois told General Pershing the Jennies ‘were not capable of meeting the present military service conditions.’ He asked for ‘at least ten of the highest-powered, highest climbing, and best weight carrying aeroplanes’ that could be provided. ‘I knew I was optimistic in thinking I would get the planes I wanted, but I was duty bound to ask for them,’ Foulois is quoted as saying. While he doubted he would get adequate equipment, he continued to do what he could with what he had. It was decided that the planes would be used to carry mail and dispatches between US ground units and reconnaissance flights.

One of the biggest problems with the whole mission was the hostility of the Mexican people and government. The Mexican government refused to let the US troops use Mexico’s rail system to transport men and supplies. The Americans thought they were helping by chasing Villa, but Carranza’s forces, the Carranzistas, were very hostile.

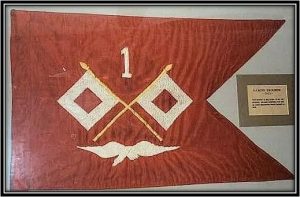

1st Aero Squadron Standard – 1913. This is believed to be the original Standard (guidon) ordered for the United States’ 1st Aero Squadron.

Photo courtesy 20th Century Aviation Magazine.

And again from History.com, “Despite numerous mechanical and navigational problems, the American fliers flew hundreds of missions for Pershing and gained important experience that would later be used by the pilots over the battlefields of Europe. However, during the 11-month mission, U.S. forces failed to capture the elusive revolutionary, and Mexican resentment over U.S. intrusion into their territory led to a diplomatic crisis. In late January 1917, with President Wilson under pressure from the Mexican government and more concerned with the war overseas than with bringing Villa to justice, the Americans were ordered home.”

So, even if you’re first, it doesn’t mean you’re going down in history as a success. I’m satisfied with being a nobody.